Join us in exploring the history of seven central Baltimore neighborhoods: Greenmount West, Charles North, Barclay, Old Goucher, Charles Village, Harwood, and Remington. This area, bounded by the Jones Falls Expressway, Twenty-Eighth Street, and Greenmount Avenue, shares a long history of growth, development, and change. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, suburban builders built blocks of new homes along Maryland Avenue, Charles Street, Saint Paul Street, Calvert Street, Guilford Avenue, and Barclay Street. Greenmount Avenue, North Avenue, and Howard Street developed into busy commercial corridors where electric streetcars and, later, automobiles and buses connected suburban residents to all parts of the city. The history of central Baltimore helps people to understand the challenges and opportunities residents face today.

Early development of central Baltimore: 1870s-1900s

Before the city annexed the area in 1818, the sparsely developed land above Boundary Avenue (now known as North Avenue) was part of Baltimore County. On the east side of the area, the Jones Falls supported early industrial development in Remington, Hampden, and Woodberry. The development of the Baltimore & Potomac Railroad in 1872 and construction of Union Station by the Northern Central Railroad in 1873 (renamed Penn Station in the 1920s) further encouraged the construction of new factories and warehouses. In 1885, the Methodist Church established the Women’s College of Baltimore City (later renamed Goucher College in 1910) at Saint Paul and Twenty-third Streets alongside the Lovely Lane Church (completed in November 1887). In 1902, after abandoning plans to develop Johns Hopkins University on the site of today’s Clifton Park, the university acquired the former Homewood estate and began to move their campus from downtown Baltimore to central Baltimore (completing Gilman Hall in 1915).

Growing community in central Baltimore: 1890s-1920s

The area known today as Central Baltimore originally developed as a suburban extension of the city. North Avenue, known as formed the border between Baltimore City and Baltimore County up until an 1818 annexation pushed the city line north to just below Cold Spring Lane. The Jones Falls formed a more persistent boundary discouraging suburban development.

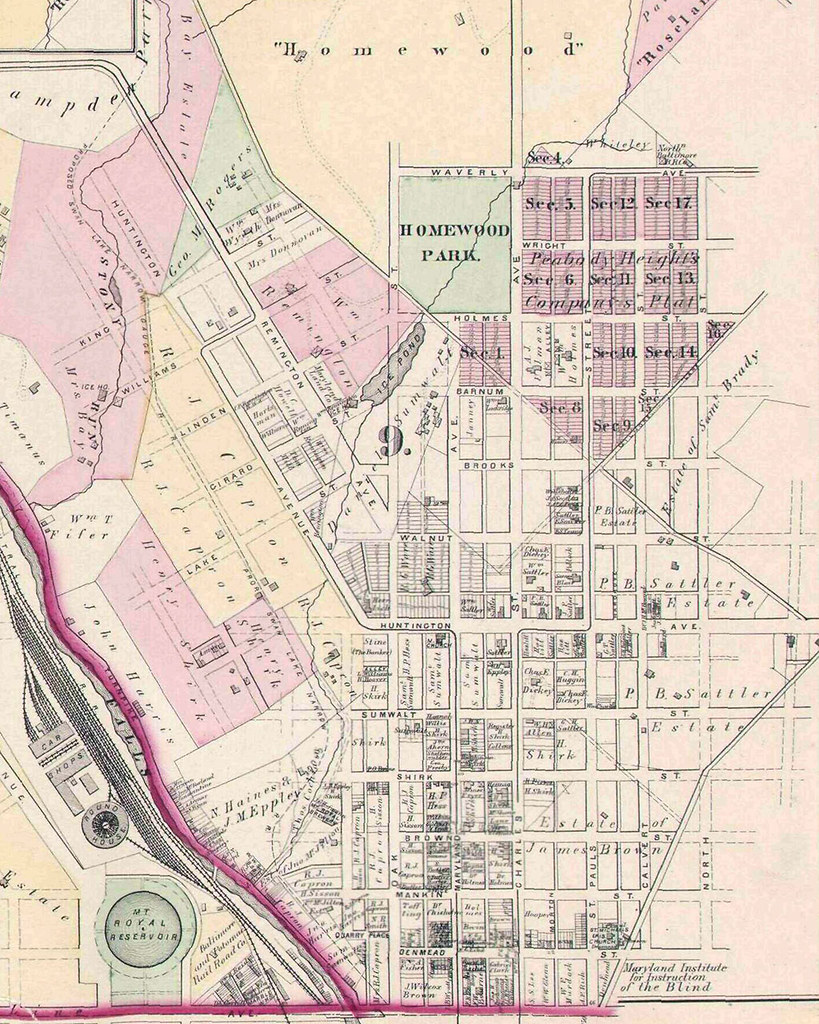

Then, in 1870, the Peabody Heights Company formed and bought fifty acres of land bordered by 27th Street to the south, 31st Street to the north, Maryland Avenue to the west, and Guilford Avenue to the east. The company subdivided the blocks into twenty-five foot wide lots and imposed restrictive covenants that required builders to erect “first class” houses set back twenty feet from the street and prohibited “slaughter houses, livery stables, manufactories, and saloons.” Ironically, the restrictions discouraged development as the city’s wealthiest residents sought detached houses in parklike and middle-class buyers could not afford homes built to the standards originally set out by the company. Finally, in 1896, the company managed to modify the restrictions and enabled a developer to begin construction in the area. Growing transportation services further enabled the area’s growth. A horse-car line on Saint Paul Street established in the 1880s turned into a cable car line, and, later, an electric streetcar that area residents relied on to travel downtown or to other parts of the city. Churches followed residents to the area including St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church (built 1898) and the Seventh Baptist Church (built 1904).

Despite the Peabody Heights Company’s efforts to promote segregation, a small population of African American residents lived in central Baltimore around the east side of Remington, near Greenmount Cemetery, and in the area of the Abell and Waverly neighborhoods. In 1870, around 1,300 black residents made up 11% of the population in the eighth ward (an area that now includes the neighborhoods of Charles North, Greenmount West, and Johnston Square).1 In 1897, a group of African American methodists organized the Oak Street A.M.E. Church and erected a small chapel at 2311 N. Howard Street in 1905. In 1898, 755 registered black voters made up just 14.1 percent of the total within the city’s 12th ward (an area roughly bounded by the Jones Falls on the south and west, Wyman Park on the west, Greenmount Avenue on the east, and E. 39th Street on the north).2

As the neighborhood grew, residents formed the Homewood Protective Association and took over the task of advocating for both segregation and a range of other shared concerns. The group worked to discourage commercial and industrial development and to seek new investments in infrastructure for residents. For example, in 1911 the Homewood Protective Association supported the extension of Calvert Street across North Avenue (where it had previously ended at the Maryland School for the Blind occupying the site where the Baltimore City Schools administration building sits today).

In the fall of 1920, a separate group of “citizens in North Baltimore” sent a letter to Mayor Broening advocating for the extension of Barlcay Street “over the open cut between Twenty-fith and Twenty-sixth streets.” In a letter dated August 15, 1923, resident Mrs. John Brunig promoted the bridge as a way to direct traffic away from 26th Street:

Mr. Swann pointed out that Charles and St. Paul streets and Greenmount avenue, and not Barclay street, are the main north and south thoroughfares in this section of the city. In baseball season between four and five hundred autors turn Barclay and Twenty-sixth streets. Sand and gravel trucks pass all day long. […] If Mr. Swann has studied this traffic, I don’t know what he is thinking of. He should see how often the autos come near striking children at this corner. If he did, maybe he would change his viewpoint.

The railroad line above 25th Street, built after the city’s authorization of the Belt Line Tunnel in 1893, also passed by Margaret Brent School at Saint Paul and Twenty-sixth streets. In July 1929, City Council member John P. Brendan for the Third District, appealed to the Mayor asking the city to “require the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to close the open cut on Twenty-sixth street, between St. Paul and Barclay streets, for a park or playground.” The appeal was successful as the playground and basketball courts adjoining the school building sit above the tracks today.

While residents above North Avenue largely succeeded in their efforts to discourage industrial and commercial development, new factories and businesses opened around North Avenue and the railroad lines passing through Penn Station. The Bell Foundry moved to Calvert Street in the late 1800s, the Crown Cork & Seal Company (now known as the Copycat Building) opened a factory on Guilford Avenue in 1897, the Morgan Millwork Company (now the MICA Graduate Center) opened around 1910, and the Lebow Building (now the Baltimore Design School) opened in 1914.

Transitions in central Baltimore: 1930s-1960s

The 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s saw a new period of change begin for the area of central Baltimore. The blocks around Charles Street and North Avenue continued to develop as a retail and entertainment destination for people around the city. The Parkway Theatre opened in 1915 followed by the North Avenue Market in 1928. In 1939, the Centre Theatre opened in a converted automobile dealership and the Times Theatre (renamed the Charles Theatre in 1959) turned a popular dance club into Baltimore’s first “all newsreel movie house.” Automobile dealerships and service stations proliferated along North Avenue, such as Eastwick Motors (now Motor House) built in 1914, and on and on Howard Street, including the Oak Street Garage in 1924 and the Eastwick Motor Company garage (now R. House) also in 1924.

The growing number of automobiles led to the construction of new roads and bridges such as the Howard Street Bridge (opened in 1938) and the Jones Falls Expressway which began construction on October 2, 1956.

Local elected officials considered a variety of proposals to convert streets in downtown and central Baltimore from two-way to one-way multiple times in the 1920s and 1930s. The change finally came in the spring of 1947 with the conversion of Saint Paul Street and Calvert Street to one-way and the creation of a “wave system” of traffic lights to speed the passage of automobiles through the neighborhood. However, a 1948 lawsuit seeking to prevent the conversion of Druid Hill Avenue and McCulloh Street to one-way featured testimony from residents in central Baltimore who saw the hazards of the change. Aimee Weber, a resident on the 2600 block of N. Charles Street remarked on the “dust, noise, dirt and gasoline fumes” and shared that the “lives of people living on those two streets have been made ‘miserable’ … many of the old residents have moved and it is impossible to sleep.”

Older white residents moving away created new opportunities for African Americans seeking housing outside the crowded black neighborhoods of east and west Baltimore. In 1927, a group of property owners in the 2200 block of Barclay Street signed a racial covenant, a legal instrument to prohibit the sale or lease of houses to African Americans that grew in popularity after the city’s failure to institute a legal requirement for racial segregation in the 1910s. A decade later, on October 22, 1936, Edward Meade, a young African-American pastor at Israel Baptist Church, inadvently tested the block’s covenant when he contracted to buy a house at 2227 Barclay Street. Owners of two other houses sought an injunction against the sale which the Circuit Court of Baltimore City granted. The state appeals court upheld the injunction leaving the racial covenants intact up until the 1948 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer.

While the end of racial covenents challenged the racial segregation of central Baltimore neighborhoods, the 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education played an even larger role in the decision of many white residents to move out of the city to the growing segregated white suburbs. Local churches and institutions were also on the move, including Goucher College which began a move to Towson in 1938 and completed the move away from central Baltimore in 1954.

The area bounded by Saint Paul Street, E. 24th Street, Greenmount Avenue, and North Avenue (census tract 0124) changed from 26.48% African American (1,441 residents of 5,441 total) in 1940 to 76.65% African American in 1960 (4,192 residents of 5,469 total). The area of Charles North and Greenmount West changed from 18.59% African American in 1940 to 57.93% in 1960. These changes were not uniform, however, as the population living in the homes on Saint Paul Street and Maryland Avenue above 21st Street and on Calvert Street and Guilford Avenue above 25th Street both remained largely white.

New organizing efforts in central Baltimore: 1960s-1980s

In the 1960s, a host of formal and informal organizing efforts began to respond to the changes and challenges that emerged in central Baltimore neighborhoods after World War II.

One notable example is the efforts of Grace Darin, an editor at the Evening Sun, to popularize a new name for the area formerly known as Peabody Heights: Charles Village. In a 1963 piece for the Sun, Darin described the origins of a “spontaneous neighborhood project” on 26th Street in the early 1950s where residents had painted four rowhouses pastel colors including one in “Bermuda pink”. Encouraged by a feature article in Gardens, Houses and People, a group of residents, including Grace Darin, began to promote the colorful paint scheme and encouraged comparisons between their block and the “bohemian” community of Greenwich Village in New York City. The block predated the popularity of the better-known “Painted Ladies” blocks in Abell by several decades as the popularity of colorful rowhouses spread through the “Painted Ladies” house competition in the 2000s. Darin described the neighborhood’s appeal, writing:

Convenience is one of our proudest boasts. We have a gourmet grocery store on one corner and a bank at the other. Witin two or three blocks are stores of all types, a library branch, a post office station, churches, schools, a hospital, sveral of the city’s better restaurants, an art film theatre, art galleries, even a folk music center.

Four years later, in 1967, Darin began to write and distribute The Charles Villager, a mimeographed newsletter that she ran through 1977 (publishing at least thirty-three editions over the decade). The new name stuck and became institutionalized with the incorporation of the Charles Village Civic Association in 1972.

Other competing and related efforts took shape at the same time. The Greater Homewood Community Corporation formed at Johns Hopkins University in 1969 and formally incorporated in 1970. The Model Urban Neighborhood Demonstration Program (MUND) operated for just three years between 1968 and 1971 but, through organizing efforts focused on African American neighborhoods in Barclay and Old Goucher, created an enduring legacy of activism. The group focused on econommic and political empowerment establishing a “community-owned carry-out seafood store on the southeast corner of North and Maryland avenues which employs local residents” and a “multipurpose community center” at Kirk Avenue and 22nd Street. In 1970, MUND presented a development plan at their headquarters at 2133 Maryland Avenue for “upgrading 150 blocks of central Baltimore” described by the Sun as “what local citizens and professional planners think should happen to the diverse deteriorated but strategic area between North avenue and 25th street.”

Cuts to federal funding under the Nixon administration ended MUND’s organizing efforts in 1971, the group left a remarkable legacy of resident leadership. Similar efforts continued in 1972 when residents organized the Harwood Improvement Association. A variety of groups carried on MUND’s mission of anti-poverty work, including several tenants’ rights organizations. For example, the Baltimore City Tenants Association had offices on East 25th street in 1979.

New federal funding led to investments in housing for low-income residents in central Baltimore including The West Twenty (now J. Van Story Branch, Sr. Apartments) at 11 W. 20th Street which opened in March 1973, Wyman House at 123 W. 29th Street which opened in February 1975, The Brentwood at 410 E. 25th Street which opened in August 1976. In 1980, Harwood was one of four neighborhoods targeted by the new Baltimore Housing Assistance Corporation for support.

Baltimore City replaced and expanded aging school buildings including an early 1960s addition to Public School 32 (later Mildred Monroe Elementary School and now Baltimore Montessori Public Charter) following the closure of nearby Benjamin Banneker Elementary School, previously known as Colored School No. 113; the construction of a new building for Margaret Brent Elementary/Middle School (1976-1977); Barclay Elementary School (1959) was expanded to include a recreation center (1976); Dallas F. Nicholas Sr. Elementary School opened (1976).

Despite these new investments, the residents of central Baltimore faced serious challenges with poverty, addiction, and violence. An August 1970 Sun profile of the area between 21st and 24th Streets, Calvert and Greenmount Avenue describes residents “caught up in the overwhelming nightmare of heroin addiction, fear and violence.” The account quotes Mary Johnson, a resident on the 400 block of E. 21st Street, explaining: “It used to be a beautiful thing living here. There were no problems.” Unfortunately, drug activity and violence associated with the trade began to dominate the neighborhood. Harry Smith, MUND’s project director, is quoted:

We’ve had a tremendous number of complaints from people in the neighborhood who are afraid to leave home at night of even sit on their steps because of the drug users.

Smith continued to describe how “Because of the water fountain, addicts congregate at the playground in the 2200 block of Hunter street. Children playing on the slides and swing occasionally find discarded syringes and hypodermic needles.” A tavern located at E. 21st Street and Guilford Avenue is described as another center for these activities and a “shooting gallery” operated out of a building across the street.

Beginning in 1971, residents with addiction may have sought treatment at the North Charles General Hospital which opened an outpatient treatment center in a row of converted rowhouses on the 2600 and 2700 blocks of N. Charles Street that year. The facility reportedly included “a community mental health center, an alcoholism center, a psychiatric day center, a Springfield State Hospital out-patient center, a well-baby clinic center” and other services.

Recent development in central Baltimore: 1990s-2010s

Many of the challenges that emerged in the 1960s persisted into the 1990s and up through the present. For example, in 1991, the Sun interviewed Mrs. Maxine Dudley, a resident of the 1800 block of Barclay Street, and shared her comments on the “heavy drug trafficking” in the neighborhood:

You can sit on the steps and hear it all the time. You can sit in your house and hear it all the time. You get used to it.

In June 1990, the Baltimore City Council approved a bill to “prohibit new private clubs and after-hours joints from opening in the Charles-North Revitalization Area.” President of the Charles North Community Association, Rev. Dale Dusman, noted that “his group rarely meets wihtout hearing complaints about nightclubs.”

There were encouraging developments with the adaptive reuse of a former Saints Philip and James School, built in 1917 at 18 West 27th Street, as the Peabody Heights Apartments in late 1993. When the Enoch Pratt Free Library announced plans to close the Saint Paul Street Branch in the mid-1990s residents organized to fight the change. In 1999, these residents established the Village Learning Place which took over operation of the building as a independent nonprofit, community library.

Historic tax credits played an important role in supporting the reuse of several significant buildings in the area. The original campus of Goucher College was designated as a National Register historic district in 1978, followed by the Charles Village and Abell in 1983. Greenmount West and Charles North became a historic district in 2002 with the creation of the North Central National Register Historic District. After a series of successful individual landmark designations and historic tax credit projects in Remington, residents organized to list the neighborhood as a historic district in January 2017.

Several new community organizations and supporting partners were established in the 2000s and early 2010s. These included the management entity for the Station North Arts District, Station North Arts & Entertainment, Inc. (2005), the Central Baltimore Partnership (2008), the Greater Greenmount Community Association (2009), and Greater Remington Improvement Association (2010). Residents and partners often organized around concurrent community planning efforts including the development of the Barclay-Midway-Old Goucher Area Master Plan (approved in June 2005), the Greenmount West Area Master Plan (approved in December 2010), and the Old Goucher Vision Plan (developed between 2013 and October 2016).

These efforts have led to significant reinvestment in central Baltimore. Since 2012, rehabilitation and new construction projects have added more than 1,000 housing units to central Baltimore. More than $600 million has been invested in redevelopment projects.